|

|

Single mother, innkeeper in California

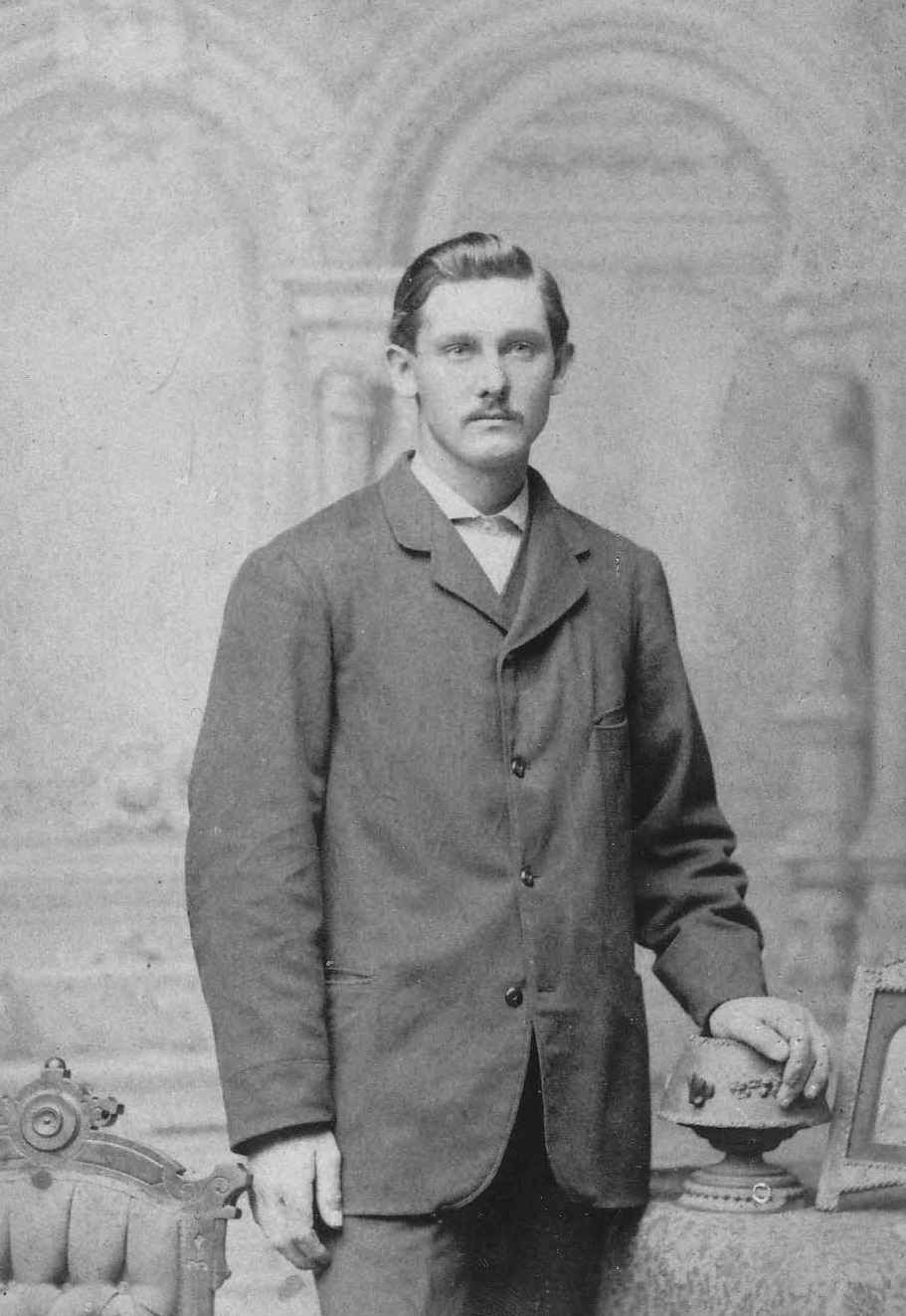

James and Ann's fourth child was Elizabeth (1866-1955), but I never heard her called anything but Lizzie. She married Lee Sherman Keithly (1864-1941) when she was about 30 years old. They had one son, James Keithly (1897-1963).

Sometime in their first ten years of marriage, Lizzie and Lee parted company. Lee remained in the St. Louis area. Lizzie headed west with little James. She was working as a dressmaker and running a rooming house in Colorado Springs when my grandparents John and Bertha moved their family to that city in 1910, hoping against hope to cure Bertha of TB.

Sometime later, probably in the 1920s, Lizzie and James moved to Redondo Beach, California, where Lizzie bought, operated, and gradually expanded a rooming house on Catalina Avenue, one block away from the attractions around the pier and harbor. She named her tourist establishment The Colorado Hotel. So far as I know from family stories, it was more like an inn, with a large dining room and about 40 rooms for mostly long-term guests. After service in World War I and a short-lived marriage, James Keithly returned to help his mother run the hotel. He stayed with her until her death, and remained in Redondo Beach for the rest of his life. He died suddenly of a heart attack in 1963, during a visit to his Aunt Loretta (see below) in Kansas City.

|

Only once did I encounter Aunt Lizzie in the flesh. It was 1954. She was 88 years old and I was 10. The photo at right shows how she looked that year, walking along the pier at Redondo Beach on the arm of her devoted son. That was not, however, where I met her. I did not get to California until 40 years later. Luckily for me, Aunt Lizzie decided in the fall of 1954 to travel one last time back to Missouri, where she still had four living siblings and other relatives. For a woman her age, this was a very big trip. Planes had not yet replaced long-distance trains. She would board the famous Union Pacific streamliner, The City of St. Louis, in Los Angeles, at noon one day, and without changing trains, arrive at her destination on the Mississippi River at noon two days later. Counting the two-hour time difference, that meant 46 hours of riding the rails by herself. Then, after visiting her St. Louis kin, she would begin her homeward journey, traveling west as far as Glasgow to visit my family, then on to Kansas City for more visiting, and to catch once again The City of St. Louis for the return to Los Angeles.

Problem was, Aunt Lizzie had become forgetful in her advanced old age, also fearful and suspicious even of her son. She had left on the trip without informing him beforehand, and she took with her for safekeeping the deeds to her properties in Redondo Beach. When she arrived at St. Louis Union Station, she rented one of the self-service luggage lockers that could be found in all major train stations of that era. She put the deeds in the locker and went off to visit her relatives. Days letter, when she departed St. Louis for Glasgow, she forgot to retrieve the deeds.

My grandparents, John and Lena, were by now no longer living on their farm, but instead in a small, two-room apartment in Glasgow. They had no room for Aunt Lizzie, and besides, Grandpa had himself become forgetful and frail. Aunt Lizzie therefore came to stay several days with us on the farm. She was a colorful, indeed overpowering presence. My sisters, single and in their twenties, asked Aunt Lizzie whether a girl should marry for love or for money. Aunt Lizzie replied without hesitation, "Money's pretty nice."

Dad brought Grandpa and Grandma out from town to visit with Aunt Lizzie in our home, but the visit did not go well. Grandpa insisted that he was older than Aunt Lizzie. She was in fact six years older than he. She corrected him in the manner of an older sibling toward a younger one. Grandpa took offense. The argument lasted a good while. I wanted to speak up for Grandpa's side of it, but even I knew he was in the wrong. This may have been the first big lesson in my young life about the horrifying ravages of age.

What was worse, so Aunt Lizzie told Mom, a man had watched her deposit her deeds in the locker in the St. Louis Union Station and then stolen the key from her, so that he could take the deeds and lay claim to her property. He would probably have done so by the time she got back to Redondo Beach, so that she would have no home or hotel to return to. Aunt Lizzie was therefore in a state of deep distress – "fit to be tied," as was said at that time.

In crisis situations, my mother could sometimes take charge with shocking decisiveness. "Aunt Lizzie," she commanded, "empty out your purse on the dining room table." Aunt Lizzie hesitated but then, seeing the look on Mom's face, meekly did as she was told. I watched the way a child does when Something Important is going on. Everything seemed to fall silent in our farmhouse. The purse seemed very large, with all kinds of things in it. Mom went through the items slowly, one by one. In that way she discovered, tied into a corner of a handkerchief, the key to the locker where Aunt Lizzie had put the deeds. "Is this the key?" Mom asked. Aunt Lizzie said it was.

I do not know exactly how Aunt Lizzie was reunited with her deeds. I remember that Mom made a long-distance telephone call to St. Louis Union Station. Such calls were expensive, never made except in emergencies. Somehow, by the time Aunt Lizzie left Kansas City for the long train journey back to California, she once again had the deeds in her possession and felt sure her property would still be there for her when she got back to Redondo Beach. She died there the next year, on November 14, 1955. Grandpa died in the little apartment in Glasgow six weeks later, on December 26, 1955.

|