(5)

Ambition |

The most surprising document in the collection is a rambling missive from John dated January 29, 1900. Fritz was already ordained by then, as John would be two years hence. The “brother” in the salutation is George, the “sister” is his wife Anna, “mother” is of course Theresia, and the “grandchildren” are George and Anna’s offspring. The two other brothers, Henry and Hermann, were probably living on their own by this time.

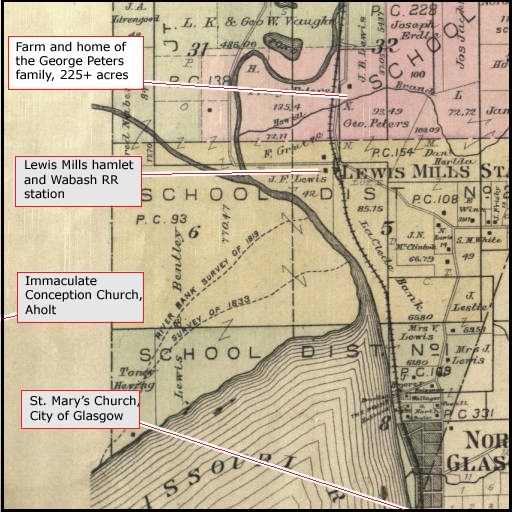

To understand John’s musing about his future, it helps to know that the Peters home lay just east of the Chariton River, placing the family by canon law in the Archdiocese of St. Louis and its local parish, St. Mary’s in Glasgow. The community the Peters family was part of, however, German Catholics farming the rich bottomlands, lay mostly on the other side of the river, which was part of the Diocese of St. Joseph and its local parish, Immaculate Conception. This parish had its own pastor, appointed by the Bishop of St. Joseph. Its small, frame country church in the hamlet called Aholt was two miles from the Peters home, the same distance as St. Mary's Church in Glasgow.

This location mattered to a bright, ambitious young man contemplating life as a priest. St. Louis was then the fourth largest city in the United States, a rich, burgeoning, cosmopolitan metropolis preparing to host both the summer Olympics and a World’s Fair in 1904. St. Louis was where the action was. The archdiocese covered half the state, of course, which meant a priest could easily spend his whole life in out-of-the-way small towns, but he could hope at least to be assigned to the cathedral city. The Diocese of St. Joseph, by contrast, was small and almost entirely rural. Nothing about its cathedral city was world-class. Relative to St. Louis, it was the boondocks.

From all the correspondence I have reviewed, it is plain that Fritz and John Peters were oriented to St. Louis as opposed to St. Joseph. They wanted to move up in the ecclesiastical world. There is no hint anywhere of interest in studying for the Diocese of St. Joseph. Indeed, as the letter below shows, John’s worry was that even in the Archdiocese of St. Louis, escape from the countryside was by no means guaranteed.

By the way, I might just as well have left my spirit in Boston and died there without any legacy as dying later in the “Missouri backwoods” [John writes this phrase in English, the only English words in these letters] in some bleak farming community. I'm talking about "backwoods,” where else should the bishop put a onetime farmer? You know what Bishop Burke [of St. Joseph] has done with a onetime coachman [the pastor at Aholt, presumably]. That is also right. I do not want to agitate against your pastor, just now his dignity is big, whether he is in the City of Aholt or the Cathedral of New York.

Our Professor said the other day, "Boys, in the world [that means outside the clergy] there are many bigger minds and talents than there are in the priesthood." I have known this for a long time, and have often wished that others had my profession and I could take care of theirs in the world. Also you, Brother, have better abilities than me to be a pastor. But again, this lies in God’s hands. He does not need help to carry out his will.

It is also a fact that less talented priests by no means achieve the greatest success. I am careful not to look forward to success. The success of the church is and remains always what matters, so that everyone can see success before long. I misjudged, and have given myself up to fate. Father Simon will always have a good standing with the older women, Father Fritz is attached to the youth. But how gossipy am I today! How are you doing? You were all healthy three weeks ago and you will be that way also now. We survived our exams. Now we feel free again, and can make ourselves comfortable. Another two and a half years, God willing, and I will be ordained. I think I will say my First Mass in a monastery if Father Waltermann is still in Glasgow. There is little wool in either place, but in the monastery, there is also no “shouting.”

The close relation between the Peters family and Father Pauck apparently did not extend to his successor, John Waeltermann, pastor of St. Mary’s from 1897 to 1915. The last line of John’s letter relies on a German proverb that describes sheep making lots of noise but yielding little wool. John apparently considered that there was much noise but little wool, much bombast but little substance, in Glasgow’s pastor at that time. |