The kind of novel

a mobbed professor writes

Review of Thomas Thibeault, Balto’s Nose (Ridgetop Press, 2011)

Kenneth Westhues, University of Waterloo, 2012

1

In August of 2009, when English instructor Thomas Thibeault was fired from East Georgia College, Greg Lukianoff, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), hinted that Thibeault might want to write a book about his experience. “If you were to write a novel about the abuse of sexual harassment regulations to get rid of a dissenter,” Lukianoff said in a press release, “you couldn’t do better than the real-life story of Thomas Thibeault.”

If Thibeault had taken the hint, he would have joined the many academic mobbing targets who have published accounts – some factual, others fictionalized, some rough, others polished – of being ganged up on by colleagues and managers, humiliated at work, and driven from their jobs. The typical mobbing makes for a compelling story, with unexpected twists and turns, striking glimpses of evil and of good, and people showing sides of themselves previously unseen.

I have read dozens of such books and found value in each one. Every mobbing story sheds light on the general process from a new angle, deepens our understanding of it. Thereby it broadens public awareness of a momentous workplace pathology and helps other mobbing targets escape from the debilitating illusion that “nobody else has ever gone through anything like this.” In addition, reducing a mobbing to words on paper is good therapy, a useful way for one who bears the brunt of mob rule to get out from under its crushing weight, a means of neutralizing workmates’ animosity. “If he wrote it,” Hemingway observed, “he could get rid of it. He had gotten rid of many things by writing them.”

But Thibeault did not take Lukianoff’s hint. He did indeed write a novel, but one whose plot, characters, and setting are far removed from dirty politics in a little southern school. There is nothing autobiographical about it, except at the level of overarching themes. One can read and enjoy Balto’s Nose without knowing the academic ordeal out of which it was created. Even so, knowing what the author was going through deepens one’s appreciation of the story, casts it in a brighter light.

2

What was the ordeal? The essential facts are plain.

On August 5, 2009, the faculty of East Georgia College met for a training session on the college’s sexual harassment policy. It was conducted by the college vice-president, Mary Smith. In the course of it, Thibeault asked what protections there were for a person wrongly accused. Dissatisfied with Smith’s reply, Thibeault said the policy was flawed.

Smith did not take Thibeault’s criticism lightly. He was not known on campus as a docile employee, had in fact been on the outs with the college administration already for at least a year. Smith reported her concern to the president, John Bryant Black, and began trolling for evidence that could be used against Thibeault.

Two days later, Black called Thibeault into his office. Smith was there, too. Black declared Thibeault guilty of (you guessed it) sexual harassment, without saying what he had allegedly done wrong, and gave him a choice, either resign immediately or be fired. Thibeault was then escorted off campus by police and forbidden to return under pain of being charged with trespassing.

In a series of hostile but confused letters over the next few weeks, Black informed Thibeault that his contract would not be renewed; described him as not yet fired, only suspended; informed him that a committee would advise on dismissal; reported that the committee had found in favour of suspension; said Thibeault could request a formal hearing on the charges; and finally, offered to send a statement of the charges on request.

By the end of the month, Thibeault had sought help from FIRE, which had promptly come to his defense and asked the chancellor of the University System of Georgia to intervene.

By the end of September, less than two months after the critical incident, the conniving of Swainsboro administrators against Thibeault had been exposed not only on FIRE’s website and blogs but in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Inside Higher Ed, and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. If sunlight is the best disinfectant, as Justice Louis Brandeis said, the process of disinfecting East Georgia College was underway.

On October 20, Black informed Thibeault that the charge of sexual harassment had been dropped for lack of evidence and that he was therefore reinstated to his position.

Not for long. On the issue of contract renewal, the college dug in its heals. Thibeault’s position on the faculty ended in May of 2010.

In October of 2010, Thibeault sued President Black, Vice-President Smith, and the University System of Georgia for unfairly retaliating against him for exercising his constitutionally protected right to free speech.

Not quite one year later, in September of 2011, plaintiff and defendants settled the lawsuit out of court. Thibeault did not get his job back, but the college coughed up $50K for him and his lawyer, and destroyed its files on his dismissal. President Black agreed to give Thibeault a letter of reference (good for bragging rights, perhaps, not likely much else).

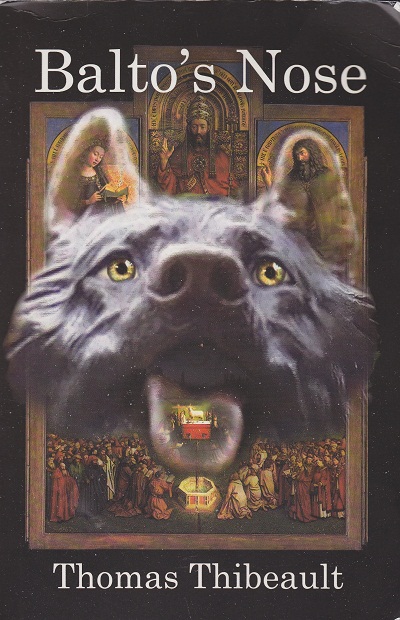

In November, legally apart from the settlement, President Black announced his own retirement after eight years in the job, and Ridgetop Press published Balto’s Nose.

3

This 350-page novel is quite something to show for two long years in the doghouse. Thibeault must surely have begun it years earlier. Nobody can dash off a work this long, thoroughly researched, and painstakingly crafted. Still, the author polished it off amidst the terror, stress and torture of a clear case of administrative mobbing. [Thibeault has since told me he wrote the book in six months of 2010. Amazing feat!]

Far from dwelling on people’s nastiness, the book is a celebration of world-historical goodness and heroism, the heights to which humans sometimes rise. It is a depiction of the “love of beautiful things in ugly times.”

About half the book is factual, drawn from the historical record: the story of the Monuments Men, the American soldiers who hunted down, rescued, and safeguarded the artistic treasures of Western civilization that the Nazis stole from countries they conquered and occupied during the Second World War.

Thibeault brings this true story alive and shows its importance by telling it coherently and in detail through the eyes of ordinary soldiers, dogfaces, assigned to the project, and by sketching the relations between them and the officers in charge. The fictional Sergeant Glenn Carnahan works closely and forms a personal bond with the real Lieutenant George Stout, just as the fictional Sergeant Jimmy Mulvaney does with the real Captain Robert Posey.

So seamlessly does Thibault weave fact and fiction that again and again I had to stop reading long enough to look things up on the internet. Did the Nazi art expert Hermann Bunjes, the Dutch forger Han van Meegeren, or the Monuments Woman Edith Standen really exist? Amazingly, in each case, yes! Is The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb a real altarpiece? Yes again, didn’t I know that before? Is there really a mine near Siegen, Germany, that the Nazis used as Thibeault says? Exactly so!

Thibeault’s genius is such that the fabrications in this book – the conversations between Jimmy and Posey, for instance, or the escapades of Glenn with Stout – are easier to believe than the things that really happened.

To enrich the story further and drive its meaning home to readers today, two-thirds of a century after World War II, Thibeault entrusts its telling to Glenn, now eighty-two years old, a retired art teacher in Brooklyn. Glenn tells it to Michael, the now adult grandson Glenn and his late wife Ellen raised after their daughter, Michael’s mother, was killed in a car accident. Actually, Glenn does more than inform Michael of what happened so many decades before. He makes Michael part of it, by taking him along to a Sotheby’s art auction where a painting Michael has seen before is on the block.

Having lots on my plate, I speed read sometimes, rush through a book to grasp its central plot and call it quits. I tried to do this with Balto’s Nose but failed. There was too much suspense, too many subplots whose resolution I didn’t want to miss. I wondered if Thibeault could possibly tie all the loose ends together in the end. By the time I finished, there were no loose ends.

4

This book was a slow read for at least two reasons more.

In 1967, a wealthy woman in New Jersey proudly showed me a painting by Rembrandt hanging in the foyer of her home. She gave me a magnifying glass to hold to it, so that I could see details that would escape an unassisted eye. With the glass I could make out veins on the hands of the people in the painting. (Years later, the painting was revealed to be a forgery. The wealthy American purchaser had been duped just as van Meegeren had duped the wealthy German air marshal, Hermann Goering. No matter. It was a first-class fake.)

That forgotten moment with the magnifying glass came back to me while I was reading Balto’s Nose. Not because the novel is in any sense fake. But it is like the pseudo-Rembrandt – and real Rembrandts – in beauty of detail. The picture is gorgeous not only overall, but even in tiny parts.

On almost every page I came across sentences I could not help but linger over and admire for their wit, insight, or loveliness. Take this metaphor: “Glenn’s eyes jumped from taxi to taxi slowly filing past the windshield and said to Michael, ‘They look like camels all tied nose to tail.’” Or this one, describing a gentlemanly officer: “smut coming out of that man’s lips would be like a nun showing you her tattoos.” Anybody drawn to artful turns of phrase will find many to revel in throughout this book.

One final thing that slowed down my reading was the intensely kind, enlivening relations Thibeault sketches between various of his characters. I found myself pondering at length the anecdotes that define these relations, then going back to reread earlier anecdotes.

Between Glenn and Stout and between Jimmy and Posey, the relation is, as much as anything, that of student and teacher – a kind of relation Thibeault undoubtedly knows well from his own experience on a college faculty. There are also the relations between Glenn and his wife, and between Jimmy and his. The reader learns of the former marriage only in retrospect, of the latter only in prospect, but both are excruciating in their tenderness and poignancy. There is also the abiding bond between Glenn and Michael, rooted in values that transcend space and time yet respectful of intergenerational difference and personal freedom.

Thibeault spends less time on character studies than on the relationships through which his characters reveal themselves. Martin Buber would approve. “The gorilla, too, is an individual,” said the German-Israeli sociologist, “a termitary, too, is a collective, but I and Thou exist only in our world, because man exists, and the I exists, moreover, only through the relation to the Thou.”

Some works of art are so rich – Balto’s Nose is one of them – that people can view or hear or read them a hundred times and still find new delights. I took my time reading Balto’s Nose, but I’m sure there are treasures in it that I missed.

5

The “ugly times” in which Thibeault finds “beautiful things” are, of course, the war that has just been won, but its ugliness is not quite over as the Monuments Men begin their work. Across a group of them admiring and discussing a statue of Venus, a German sniper lurking in a bombed-out building sweeps his machine gun, killing several before being blown to bits by return fire.

Toward the end of the novel the Monuments Men encounter a different kind of ugliness, which Thibeault describes with such visceral contempt one can tell he has encountered it in his own experience. It is the coming of the “garritroopers,” This word was new to me. I looked it up. It appears to have been coined during World War II by Bill Mauldin, cartoonist for The Stars and Stripes, to describe soldiers who lived through the war in the safety of garrisons, as compared to those involved in actual combat on battlefields and in the streets.

As Thibeault describes the garritroopers, “Serious gunfire was beyond their hearing, but they affected the style of the front-line soldier. … The officers were the worst because they had rank without risk. They were all sticklers for protocol and regulation and would demand a salute from anything that could wave an elbow.”

In the twenty-first century, Judith, Jimmy Mulvaney’s daughter, says she has seen that type in every job she has had.” Michael, Glenn’s grandson, agrees: “Yeah. Give them a title and a mission statement and they become little kings.”

In Balto’s Nose, the garritroopers complicate the work of the Monuments Men by insisting on impractical and counterproductive bureaucratic rules. Far worse, they try to undermine the achievements of the Monuments Men, subvert its noble purpose, by ordering a shipment of German artistic treasures to the United States. This would be essentially the same crime on America’s part as the German crime the Monuments Men had risked their lives to correct. Courageously and successfully, the Monuments Men resist.

In the context of Thibeault’s mobbing at East Georgia College, garritroopers have to be seen as a metaphor for the administrators who went after him: sticklers for protocol and regulation, little kings, people who possess rank but do not risk being true teachers and intellectuals.

The distinction is essential for understanding how life goes in the increasingly bureaucratized colleges and universities of our time. Kierkegaard distinguished two ways of conducting oneself in academic life: “one way is to suffer; the other is to be a professor of the fact that another suffered.” Thibeault exemplifies the first way. Balto’s Nose is proof. A student on ratemyprofessors gave him the highest rating and commented: “learned a lot and he's a weirdo.” Professors of this type arouse intense animosity in Kierkegaard’s other kind of academic, the garritrooper types. Administrative mobbing is one common result.

When I joined the faculty of the University of Waterloo as a department chair in 1975, there was a custom, an informal norm, that all administrators, including even the president and vice-president, should teach at least one course a year. The idea was to prevent the institution being taken over by garritroopers. By the time I retired from full-time teaching in 2011, that informal norm had long since gone by the board. As in most institutions of higher learning, administrators had gradually become a separate caste, removed from the exposure, risk, and suffering of engaging real students in real lecture halls.

6

I have been puzzling for years over what kinds of professor get mobbed. The question is basic to a science of workplace mobbing. Targets come in many different kinds. The odds favour anybody who, purposely or not, consciously or not, reminds workmates of who they are not. This is why veterans of combat, soldiers with the scars of suffering, are vulnerable to humiliation by garritroopers. The former show the latter up, threaten them, remind them of who they aren’t.

In the postmodern climate on most of today’s campuses, one type of professor who crops up often among mobbing targets I have studied is the kind who can’t just “go with the flow,” the kind who are convinced of a reality external to the mind and have the courage of their conviction. Less than entirely relativist and disinclined to live in quotation marks, they seem to threaten colleagues and administrators for whom truth merely shows some camp’s hegemony in a socially constructed world.

What triggered Thibeault’s firing was his disagreement with Vice-president Smith over whether an alleged victim’s perception was enough to warrant a report of sexual harassment. Reflecting a postmodern world-view, Smith said yes, that if the person feels offended, then the incident must be reported. Thibeault said no. He was worried about cases where the person’s feelings do not square with the reality of what transpired – in other words, accusations that are false.

Like its author, Balto’s Nose is foreign to the postmodern mentality. The sometimes elusive difference between perception and reality is one of the things that makes this novel so gripping, so hard to put down. A plausible account of something turns out, pages later, to be an illusion. Again and again, the reader has the pleasure of discovering that what initially looked true is actually false, or vice versa.

But such pleasure depends on knowing that some things really are true or false, that not everything depends on opinion or power. This novel is about a real world wherein people kill and are killed, betray trust and live up to it, speak honestly and lie, behave as heroes and as cowards.

The “Balto” of the book’s title was the lead dog of a sled in Alaska in 1925, that traveled 660 miles over treacherous terrain to bring medications to people sick with diphtheria in Nome. There is a bronze statue of him in New York’s Central Park. So many kids rub Balto’s nose that it looks, in Thibeault’s words, like a “gleaming beacon that would have made Rudolph jealous.”

Ever since Michael was a boy, Glenn has been taking him to the statue of Balto in the park for a lesson in courage. To grasp how far this novel is from the postmodern spirit, and how close to the classic values of Western civilization, note how Thibeault describes Michael’s reaction to these wintry trips his grandfather takes him on: “What Michael liked best about Balto’s nose was that Balto had been a real, live dog. Rudolph was just a made-up Santa story. Rudolph would fly away into the clouds when children outgrew Santa Claus, but Balto would stand scanning the distance in Central Park forever.”

If the playing field between truth and fantasy were leveled, Balto and Rudolph put on a common plane, and the title on the next printing of this novel changed to something more playful like Rudolph’s Nose, the point of all these pages would be lost. There is lots funny in this book (much of it guy humor of the kind soldiers like), but Thibeault wants us to believe, as he does, that life is serious, not just a game.

7

On first learning that Thibeault was producing a novel out of the bizarre process of his elimination from the faculty of East Georgia College, I expected that it would be some kind of take-off on his experience, probably an allegory of the administrative mobbing he underwent. That would have been a fitting project to undertake, many previous mobbing targets had pointed the way, and FIRE’s Greg Lukianoff had as much as suggested it.

Maybe Thibeault will yet produce such a novel. His talent is such that he would make a good job of it.

In the shorter term, the literary outcome of his years of grief is a nobler and more powerful work of art. Thibeault didn’t “let the turkeys get him down,” even to the extent of modeling characters in his novel after them. He ignored them and rose above their petty chicanery. Balto’s Nose is the more beautiful a work of art, for having been written amidst destructive ugliness.

How lucky students in rural Georgia were to have as their English teacher an author of Thibeault’s caliber! How incompetent, how unworthy of their jobs, were the administrators who conspired to dump Thibeault on fabricated grounds!

If he watched the 2012 Grammy Awards show, I wonder if Thibeault identified with the lyrics of Taylor Swift's song: "Someday, I'll be big enough so you can't hit me (Why you gotta be so mean?)."

Maybe not. Publication of Balto’s Nose shows that Thibeault is that big already.