Henry J. Westhues

(1888-1969)

as a young lawyer

HOW UNCLE HENRY UPSTAGED

THE OUTBREAK OF WORLD WAR

Kenneth Westhues, 2012

Click here for a larger image.

Click here for a larger image.

|

Click here for a larger image.

Click here for a larger image. |

|

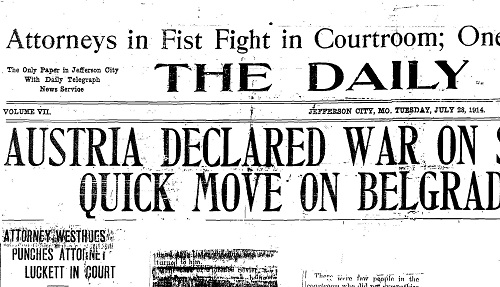

Well, not quite! The biggest headline in The Daily Post of Jefferson City, Missouri, on July 28, 1914, was for Austria's declaration of war on Serbia, the action that officially started World War I. But that headline came second on the newspaper's front page. The lead headline, the one at the top, was Uncle Henry's doing: "Attorneys in Fist Fight in Courtroom; One Knocked Into Jury Box."

The incident is worth remembering for the insight it gives into how the culture of that era differs from ours a century later. Then as now, physical violence was rare in a court of law. Otherwise, this instance would not have been such big news. Yet violence did not receive such blanket condemnation as today. Four years after slugging the opposing counsel in court, Henry Westhues was elected prosecuting attorney of the county that includes the state capital. In 1922, he was elected judge of the circuit court. From 1930 until his retirement in 1963, he was on the state supreme court, first as commissioner, then as judge, finally as chief justice. Socking another lawyer in the jaw clearly did little long-term damage to Henry's career. He rose to higher positions than any observer would have predicted, especially given his birth in Germany, German first language, upbringing on a farm, and education mainly outside of school. In 1914, of course, nobody knew what would become of the young lawyer. He was 26 years old, as yet unmarried. He had completed his studies at St. Louis University two years previous, moved to the state capital, and wangled an appointment as attorney for the city government. The case that brought him to court on July 28 was the kind with which courts are clogged even today: a woman of ill repute charged with unprovoked assault of another woman. Young Henry and the county prosecutor were pleading the case for her conviction. Defending her was a man twice Henry's age: Fenton Luckett, 53 years old, a former prosecuting attorney with an established reputation in criminal law. Here is The Daily Post's account of what transpired: |

|

Attorneys in Fist Fight in Courtroom; One Knocked Into Jury Box |

|

What is most noteworthy about the news report, written in haste on the day of the event, is how slanted it is in Uncle Henry's favor. It says the two attorneys "engaged in a fight," yet there is no indication that Luckett landed a single blow or even took a swing. The physical aggression appears to have all been on Uncle Henry's part. He "drove his fist squarely against Attorney Luckett's jaw," knocking him into the jury box, and "was so enraged that he would probably have followed Luckett up" had the sheriff not intervened. The term "fist fight" in the lead headline does not square with the text. This was not a fist fight. It was an assault by one lawyer on another.

Also remarkable is the asymmetry between Florence Sevier's punishment for assaulting another woman and Henry Westhues's punishment for assaulting another man. Mrs. Sevier got a $50 fine and thirty days in jail. Mr. Westhues got a $5 fine, which was promptly cancelled— in other words, no punishment at all. To help us understand how the incident played out, we have the three interesting further paragraphs of The Daily Post's article: |

|

There were few people in the courtroom who did not sympathize with Mr. Westhues. Having his name linked with that of the woman on trial is no laughing matter and no man with red blood in his veins would let such an insult go by unchallenged. Mr. Luckett is not usually guilty of such accusations as he made today and we like to think that his assertion came out in the heat of argument and that he really did not mean what he said. |

|

From this editorializing at the end of the news report, we can fairly conclude that in the culture of that era, there was a crucial difference between Mrs. Sevier's assault and Mr. Westhues's. Hers was understood to be "for no cause or reason" (the details were not reported) while his was almost a duty: "no man with red blood in his veins would let such an insult go by unchallenged." Red-blooded, according to dictionaries, means healthy, high-spirited, vigorous, lusty, strong-willed. In the newspaper's view, ignoring Luckett's insult would have exposed Uncle Henry as a wimp.

The further difference between the two assaults was in the perpetrator's respectability. Mrs. Sevier, who might be described in today's press as a "sex worker" and "victim of police repression," was instead referred to as "the Sevier woman" and portrayed as beneath contempt. The young lawyer, who today might be seen as arrogant and having "anger-management issues," was instead said to be "a gentleman in every particular" with a reputation "beyond reproach." Although the newspaper report does not use the word, one can fairly infer that popular culture in Missouri in the early twentieth century still placed considerable value on honor, a concept about which Margaret Visser has written insightfully (see also the Nisbett/Cohen book, The Culture of Honor). By honor is meant one's good name or social standing in a community, in defense of which one may be required to take direct action, regardless of law or state authority. This is essentially what Uncle Henry did in his instant physical attack on an opponent engaged in smearing Henry's name and standing in the Jefferson City community. He took the law into his own hands, to a degree less tolerated today. By now in North America, a culture of honor has generally given way to a culture of law. What Uncle Henry might better have done, from this point of view, was hold his temper, refrain from violence, and sue Fenton Luckett for defamation. In today's more cynical time, some readers of this account may wonder whether perhaps Mr. Luckett's accusation was true, that Henry Westhues had indeed been intimate with Florence Sevier. Well-publicized instances abound in recent times of prominent men haughtily denying sexual indiscretions that were later shown to be true — President Bill Clinton, Senator John Edwards, Representative Anthony Weiner, many more. Regrettably, there is no way in this year of 2012 to prove conclusively that Sevier and Westhues did or did not have a liaison back in 1914. For what it's worth, my firm belief is that Fenton Luckett's accusation was false and that the anger of the accused was unfeigned. So far as I knew Uncle Henry in the 1950s and 1960s, his conduct was governed more by conscience and honor than by law. Compared to a Clinton, Edwards, or Weiner, he was a throwback to an earlier time. One final observation is in order on The Daily Post's lead story the day World War I commenced. The newspaper crafted its report on the courtroom violence in a way that demonized neither of the men involved. It went out of its way to rationalize Uncle Henry's attack on Luckett, but it also refrained from casting the latter in a negative light. Luckett might have been called, for instance, a scurrilous slanderer. Instead his slur on Uncle Henry was described as being out of character, uttered "in the heat of argument" without real conviction. Thereby the newspaper upheld the honor of both men (Mrs. Sevier did not fare as well), made the best of a sorry turn of events, and encouraged an ethic of live and let live. The twenty-first century press could take a lesson. |

|

With thanks to my cousin Otto Rieke II and to my brother James F. Westhues for drawing my attention to the 1914 newspaper article. The commentary, of course, is entirely my responsibility. Email comments and additional reflections, critical or otherwise, for possible inclusion on this webpage. Numerous reflections on Henry J. Westhues in his mature years are included in an autobiographical work by one of his grandsons: Otto Rieke II, From Grief to Glory (Authorhouse 2011; preview available on the author's website). |