|

New in 2016,

More information on the Peters Family:

Beware the Missouri Backwoods, Letters Home from Fritz and John, 1894-1900

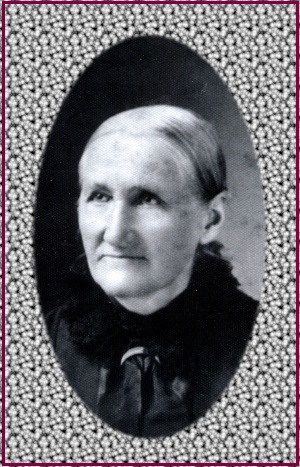

Theresia Peters

Kenneth Westhues 2013

|

|

New in 2016, Beware the Missouri Backwoods, Letters Home from Fritz and John, 1894-1900 |

|

The first of my paternal ancestors to move to the New World was my great-grandmother, Theresia Peters (1834-1907). Her story is of interest first of all to her hundreds of descendants. Many of them, bearing her own surname, are progeny of her sons George and Herman, their sons and grandsons. Many others, including me, bear the surname of Wilhelm Westhues, husband of her daughter, the younger Theresia. Still others bear the names of the men her granddaughters married: Flaspohler, Oidtman, Michel, Deken, Lampe, Hirtz. There are dozens more surnames among Theresia's descendants in later generations. For many of them this webpage will be a first opportunity to know Theresia's name, see her picture, and learn something of her life. Her story is of wider interest for her family's unusually close attachment to the Catholic Church and its leadership role in the foundation of Catholic institutions in Missouri, most notably the parish and community of Glennonville, Dunklin County, in the state's far southeast corner. Like most Christian religious bodies, the Catholic Church has dwindled drastically in personnel, prestige, and influence over the past half century. The Peters family, from its arrival in 1888 until the First World War, is a good case study of the importance of institutional religion in that era, a benchmark against which to assess the decline of Catholicism more recently. Lest the current secular age become a prison for us who live in it, we need to keep ourselves aware of the intensely religious ways of life Americans followed a century ago. |

Click here for information about and photos of the family of Theresia Peters's only daughter, also named Theresia, who married Wilhelm Westhues, was the mother of ten children, and lived all the rest of her life, after the migration to America, on her and Wilhelm's farm near Glasgow, Missouri. |

|

|

The Münsterland origin The essential fact for understanding the Peters family is that they came not just from Germany, but from a distinct, deeply Catholic region near the Dutch border in mainly Protestant Prussia, or the northern part of Germany. This region, Münsterland, has been a separate political and ecclesiastical entity for 1200 years, since St. Ludger was installed as the first bishop of Münster in the year 805. Today, the region is one of the five administrative districts of the German state of Nordrhein-Westphalen. It is linguistically distinct, traces remaining even now of the Low Saxon dialect (the hues in my surname is the local word for the German haus, the English house, or the Dutch huis). Catholicism in this region lacks the Gemütlichkeit of Bavaria but is no less firm or fierce. In the nineteenth century, the church was taken for granted and cherished as the foundation of society, much as in Ireland, Quebec, or Spain at that time. The best indicator of the strength of Catholicism in Münsterland dates from the Nazi period, half a century after the Peters family left. The bishop of Münster at that time, Clemens von Galen, publicly and repeatedly denounced the Hitler government in the name of Catholic teaching. Von Galen was arguably the most outspoken critic of Nazism among the 25 Catholic bishops in Germany. And he got by with it. Hitler rejected advice to imprison or execute him, fearing popular rebellion in Münsterland if the Gestapo arrested its spiritual leader. Pope Pius XII named von Galen a Cardinal after the war and he is now a candidate for sainthood. Theresia Dilkaute Peters lived in a simpler time, making her life with her husband, Johann, on a farm near Haltern, a town along the Lippe River 30 miles southwest of Münster. Almost certainly they owned (as opposed to rented) the property, since both her mother and Johann's mother had inherited farms. The main trauma in her life was familial rather than political. In 1876, at the age of 51, Johann died, leaving her with seven children. Theresia, the eldest, was 16. John was not yet a year old. In keeping with the established norm of male primogeniture, the eldest son George assumed the role of paterfamilias (his posture and stature in the photo above suggest how seriously he embraced this responsibility). By 1888, George was 25, still single. Daughter Theresia had married and left home. Second son Joseph was away in military service. Youngest son John was 13. That was the point at which the family decided to sell out and move half a world away, to a small town in the centre of Missouri, USA. Relatives and friends from the Haltern area had already migrated there and sent back positive reports. |

Click here for historical information about Glasgow and the Boone's Lick region of Missouri. |

The Missouri Destination The counties of mid-Missouri were settled in the early nineteenth century mainly by Americans from Virginia and Kentucky, who established a slave-based plantation economy. The region came to be called Little Dixie. The town of Glasgow, laid out in 1836, was a port on the Missouri River from which local agricultural products, chiefly tobacco and hemp, were shipped downstream to eastern and international markets. During the Civil War of 1860-1864, the society and economy of the Glasgow area collapsed. Crops did not get planted. Bushwhackers robbed banks, disrupted trade, ransacked food supplies, and murdered soldiers and civilians alike. For their part, Union militiamen and troops garrisoned in Glasgow and nearby towns wreaked vengeance on Southern sympathizers. Lawlessness, savagery, and destruction made the Glasgow area a place that residents, especially from the propertied class, would want to move away from if they could. The upshot was good farmland and substantial homes available at fire-sale prices. For years and decades after the war, the relatively low cost of real estate, along with the American promise of political and religious freedom, attracted German immigrants to the area. They were unmoved by the hatreds of the war and intent only on creating prosperous New-World versions of the ancient rural communities they came from in Europe. In the final third of the nineteenth century, a community of roughly 200 Catholic families, mainly of German origin, took shape in the hills and floodplains north of Glasgow. Its centre was St. Mary's Church, built at the corner of Third and Howard Streets in 1866, along with its parochial school. The current church, a large and imposing neo-Gothic structure, dates from 1912. Theresia Peters and her sons arrived toward the end of the chain migration of Münsterlanders to Missouri. The 160-acre farm they bought and worked was just at the edge of the Chariton River bottoms, their house being on high enough ground to be safe from periodic floods. Two years after they arrived, George married Anna Ridderman (1872-1919), the Missouri-born daughter of immigrants from Hiddingsel, Münsterland, who had come just after the Civil War. The marriage took place at Immaculate Conception Church in Aholt, a parish in the bottomlands later absorbed by St. Mary's in Glasgow. |

|

Into the arms of the church By Catholic teaching, priests are on a higher plane than laypeople. Hence, to be the mother of a priest is one of the greatest blessings a woman can receive. It is an honour, a basis of respect and prestige. Theresia Peters became the mother of not one but two priests. Son Fritz began his collegiate studies at a school in Quincy, Illinois, run by Franciscan Fathers from Germany (it is now called Quincy University) in 1890, just two years after the arrival in America. He completed his theology training at Kenrick Seminary in St. Louis, and was ordained a priest of the St. Louis Archdiocese in 1898, shortly after his twenty-fifth birthday. Theresia's youngest son, John, after flirting with professional baseball, followed in Fritz's footsteps, and was ordained in 1902. |

Click here for a photo |

|

Click here for Fritz Peters's first-person

Click here (or scroll to the end of this essay) for an annotated list of eight accounts of the colony's history, three of them available online. |

Archbishop Glennon's plan for Father Fritz Father Fritz's first assignment was as curate and prison chaplain in Jefferson City. Then in 1905, at the age of 32, he was given an extraordinary commission that would consume the rest of his life. The commission came from the vigorous young Archbishop of St. Louis, John Glennon, who had begun his 42-year tenure in that post two years earlier. A native of Ireland, Glennon made it his goal to replicate European Christendom in Missouri, building institutions under church control for all aspects of people's lives — churches above all but also schools, colleges, universities, hospitals, social clubs, sports organizations, newspapers, social-welfare agencies, and more. So great was his success that St. Louis came to be called, "The Rome of the West." Glennon was made a Cardinal at the 1946 consistory at which Münster's von Galen received the same honour. One of the more exotic institutions Glennon established was a colony of Catholic farmers in "Swampeast Missouri," the sparsely populated lowland between the Mississippi and St. Francis Rivers in the southeast "bootheel" corner of the archdiocese. Colonization projects for settling as yet unoccupied territory were common on the American and Canadian frontiers throughout the nineteenth century. Many of these were purely financial ventures. An entrepreneur would buy a large tract of land and then sell farm-sized parcels to colonists from Europe or eastern regions looking to make a fresh start. Many other colonization projects had a religious or cultural dimension, geared to colonists of a specific faith or ethnicity and promising the chance to form new communities and relations of mutual aid with like-minded people. Glennon's project was of the latter kind. Catholicism was partial to rural life, considering it less threatening to faith than urban settings. Partial, too, to distinctly Catholic communities whose homogeneity was a buffer against Protestant influence. Glennon was also eager to establish a Catholic presence in all regions of the archdiocese, including the overwhelmingly Protestant southeast, which had so far attracted few Catholic immigrants. Thus did Glennon buy 12,500 acres of flat, wet timberland, and assign Fritz Peters to lead the colonization project. Father Fritz would be pastor, planner, promoter, defender, recruiter, land agent, school superintendent, and overall shepherd of the community, which was envisioned to contain about a hundred families. They would be predominantly German (Glennon intended a separate colony nearby, named Wilhelmina, for Dutch Catholics). Nothing in the historical record suggests enthusiasm for this commission on Father Peters's part. He had aspired to be a priest, not a frontiersman. After moving from Münsterland to Glasgow, then studying in Quincy and St. Louis, then working in the state capital, he was now being sent to the boondocks, charged with turning 20 square miles of uninhabited wooded swamp into an economically viable and religiously faithful Catholic community. In November of 1905, he surveyed the tract on horseback and reported back to Glennon that while he thought a success could be made of the Colony, it would mean "a heavy expense and still heavier labor for me and the Colonists." Glennon replied that he knew this was work "not perhaps becoming a priest, yet I would kindly ask you to undertake the work and to reap the benefits as long as you will." I suspect there was more to naming the colony Glennonville than simply honouring the St. Louis archbishop. Father Fritz named the church and parish St. Theresa's, presumably in honour of his mother. One might have expected, as was common in Catholic regions of Europe and North America, that the settlement or town would take the name of the parish with which it coincided. Why did Father Peters depart from this convention? My hunch is that the name Glennonville, while obviously honouring the archbishop, had an element in it of, "Don't blame me." The colony was Glennon's baby. Fritz Peters was but an instrument of the archbishop's will. I suspect he wanted the name of the place to drive that point home. He never claimed to have hatched the idea of the colony nor to have been eager to lead it. "I was obedient," was the most he would say. Even so, he accepted the commission with grim determination to succeed and willingness to work alongside the other colonists at whatever needed to be done. He recruited eventually about a hundred families. The challenges and hardships they faced were typical of frontier settlements. Logging and lumbering were the first industries, agriculture having to wait until the land was cleared. Prosperity eluded the colony, but it survived. A simple frame church was built in 1908, later a parish hall, with elementary and high schools. Some founding families moved away; others moved in. The population eventually peaked at about 400. |

|

Additional founding colonists: Theresia, George, and Henry I have not been able to learn from written records or family folklore why Father Fritz's mother and two of his older brothers decided to pull up stakes in Glasgow and move to Glennonville. Did the young priest beg them to join him in the boondocks, or did they volunteer? It is hard to believe they saw better economic prospects in Glennonville than in the Glasgow area. On the contrary, the move promised little besides privation, hard work, and a good chance to catch malaria. George was married by then, with seven children under fourteen years of age. My best guess is that like their brother Fritz, George and Henry discerned the voice of God in Archbishop Glennon's call to found the Catholic colony. Answering that call was a way of living out their faith. |

Click here for a larger image, with each person clearly identified by name and dates of birth and death — it is reproduced with the kind permission of Darrall Hirtz. |

|

Descendant JY Miller |

The Peters family was one of at least three from the Glasgow area to move to Glennonville, the others being Fortman and Fuemmeler. The Peters wasted no time, arriving in the fall of 1906, a year after Father Fritz's initial ride across the tract. Glennonville was a life sentence for Fritz Peters, but for his mother Theresia, it was a death sentence. She was 72 years old at the time of the move. In the colony she lived with her son Henry, probably in a log structure. She died a year later, on October 4, 1907. Her body was returned for burial to Glasgow, where her daughter (Theresia Westhues) still lived. Attesting to the strength of the hold the colony had on its founding families, all or virtually all of George and Anna's eight children found husbands or wives from the colony and lived there all their lives. Most had large families, and many of their descendants live in the area even now. Henry Peters never married. After a rectory was constructed next to the church, he lived with Father Fritz in the modest frame structure until his death in 1932. In the organization of the American Catholic Church, it has been common even since the nineteenth century for pastors to be transferred from one parish to another every five or ten years. It is a way of preventing attachment to a specific parish from compromising a priest's loyalty to the church. In Father Fritz's case, attachment to Glennonville embodied rather than compromised his ecclesiastical loyalty, and so Archbishop Glennon left him there. Glennon's successor, Archbishop Joseph Ritter, rewarded Father Fritz with the title of Monsignor in 1949. He continued as pastor until his death in 1956. |

|

|

Click here for a review of the parish's achievements by 1952, and here for the parish's current website, with photos of the impressive parish plant. |

Archbishop Glennon's plan for Father John When John Glennon took charge of the St. Louis Archdiocese in the fall of 1903, the career of newly ordained John Peters had already been pointed in a very different direction from that of his brother Fritz. Glennon's predecessor had appointed Father John as assistant pastor of St. Francis de Sales Parish in the city of St. Louis. This was not only an urban parish, but one of the largest and most prosperous of the archdiocese, established to serve the immigrant German community. Because a tornado had destroyed the parish church, a high priority during Father John's time there was to build a new one. In 1907, he laid the first brick for what would become a stupendous neo-Gothic church modelled after the cathedral of Munich, Germany. It is still in use, referred to locally as the "Cathedral of South St. Louis." Renamed St. Frances de Sales Oratory, it is today the archdiocese's single main centre of traditional Catholcism, with liturgical practices typical of the era before the Second Vatican Council of 1962-1965. Were Father John to come back from the dead and visit the parish he left a hundred years ago, he would feel at home. In 1913, Glennon entrusted Father John with a parish of his own, but not an existing one, commissioning him instead to establish a new parish for the growing German-immigrant community. It would be on Delor Street, three miles south of St. Francis de Sales along Gravois Avenue. Father John cannot be called a colonist. The territory for his new parish was not uninhabited woodland but a long settled area then on the outskirts of the state's largest city, in transition from farmland to residential neighborhood. He had no need to recruit parishioners. They were moving to the area of their own accord, for housing in the burgeoning metropolis. Even so, Father John's commission was similar in some respects to his brother's: he was to create a parish community with a range of institutions that would anchor its members and preserve their faith in the larger, mainly Protestant culture of America. Father John met that challenge in spades. On the occasion of dedication of the new St. John the Baptist Parish Church in 1925, Archbishop Glennon publicly declared: "I don't know that any congregation in the diocese, or any priest in the diocese, has done better than your pastor and this congregation. I don't know of any that have achieved so much...." The church was more modest than the one at St. Francis de Sales, but not by much. Its architecture is Italian Romanesque Revival. Schools, rectory, convent, and auditorium were built to match. |

The photo of John |

|

|

Like his brother in Glennonville, Father John was permitted to remain his whole life in the parish he founded. By the 1950s, three assistant pastors were on staff. It is a bit of a puzzle that he was never named Monsignor. It may be that he died too soon — in 1955, shortly after his eightieth birthday. |

|

Hermann Peters's life apart The son of Theresia Peters least closely tied to the church was Hermann, though he did not stray far. In 1902, the same year John was ordained a priest, Hermann married Mary Tihen, daughter of a prominent Catholic family in Jefferson City. Mary's brother John Henry was a priest, later bishop of Lincoln, Nebraska, and then Denver, Colorado. Hermann was a groceryman in Jefferson City. He and Mary adopted two children. She died in 1938, at the age of seventy-one, but he became the longest lived of Theresia Peters's sons. He died at a nursing home near Jefferson City in 1958, at the age of eighty-eight. |

Click here for photos of and information about Father Joseph Westhues, Theresia's grandson. Click here for a photo of Father John Westhues, Theresia's great-grandson, standing alongside her two priest-sons, Fathers John and Fritz, with two pretty little girls in front. |

Religious life in later generations Not surprisingly, the closeness to the church of Theresia Peters's children persisted through subsequent generations. One of her grandsons, Theresia and Wilhelm Westhues's son Joseph (1884-1938), traveled much the same path as his uncles Fritz and John, studying first with the German Franciscans in Quincy, IL, and then at Kenrick Seminary in St. Louis. He was ordained a priest of the St. Louis Archdiocese in 1907. After a series of short-term assignments and a ten-year stint as Assistant Pastor at Holy Trinity Parish on North 14th Street, Father Joe was commissioned in 1921, to found a parish in the new northern suburb of Riverview Gardens. He remained there until his death in 1938, at the age of 54. A modest street near the church he built continues to bear his name, Westhues Way. In the next generation, two of Theresia Peters's great-grandsons became priests: John Henry Westhues (1922-2008), ordained in 1948, named Monsignor in 1957, long-time Chancellor, Vicar-General, and Pastor in the Diocese of Springfield-Cape Girardeau; and Glennonville native Nicholas J. Hirtz, ordained in 1957 for the same diocese. Four of her Westhues great-granddaughters have spent their adult lives in religious communities: Marjorie (Sr. Joan Cordis) in the Maryknoll Sisters, Mary in the Cenacle, Cecilia ( Sr. Anita Marie) and Katherine Mary in the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth. A fifth great-granddaughter, Elaine, spent many years in the last-named community. I do not know how many of Theresia Peters's great-granddaughters in Glennonville became nuns. Nor do I know how many of her later descendants there have entered religious life. One of them, Joseph Weidenbenner, was ordained a priest of the Springfield-Cape Girardeau diocese in 2007, and is currently pastor of the parish in West Plains, MO. I suspect that at least half a dozen of the roughly thirty young women from the Catholic colony who became Sisters, descend from her son George. In a larger sense, Theresia Peters can be regarded as the mother of the colony itself. |

|

Personal connection I should note in conclusion the closeness felt in my immediate family to Theresia Peters and her sons. They were the uncles of my father, John Westhues. George's children were his agemates. Dad recalled with much pleasure his visits as a boy to George and Anna's home, before they moved to Glennonville. My impression is that Dad's father Wilhelm (the younger Theresia's husband), while deeply Catholic, was flintier, more hard-nosed than the Peters men, and more intent on getting ahead economically. Besides, he had an aversion to swampy land. Dad's older brother William, twenty-five years old and as yet unmarried when Father Fritz started the Glennonville colony, had wanted to join it, but Grandpa Wilhelm said no. As the twentieth century wore on, the ties of Wilhelm and Theresia Westhues's family to the Peters relatives in Glennonville were not much closer than its ties to the Westhues relatives in Germany. My father, however, never lost his feeling of closeness to the Peters relatives. He disliked traveling away from our farm, but in 1953, he gladly let my older brother Gene drive him, Mom, and me for a visit to Glennonville. For the rest of his life, Dad appreciated how warmly we were received by his uncle and cousins. Similarly, I remember as an eleven-year-old being shocked at how quickly and firmly Dad declared we would attend Father John's funeral in St. Louis, when news of his death came in 1955. The Peters family represented for me, as I was growing up, a kinder, gentler variant of German-American culture than the Westhues variant around Glasgow. |

|

|

|

1. Sister Rebecca White, OSU, "Rare and Impossible Things: Glennonville and Ursulines Celebrate a Long History Together," Ursulines Alive (4:6, summer 2006). Father Peters entrusted the colony's schools to the Ursuline Sisters of Maple Mount, Kentucky. More than a dozen local girls then joined this religious community. Its bond with Glennonville runs deep. I am grateful to Darrall Hirtz for permission to reproduce here the portrait photo of Theresia Peters. The holy cards reproduced here were kindly sent to me by Mrs. Theresa Hefner, granddaughter of George and Anna Peters, in 1999. In 2013, the pastor at St. Mary's Church in Glasgow accepted the holy cards relating to this parish for preservation in its archives. |